Why Try-Fail-Learn-Repeat?

In 2018, I decided to call my blog "Try Fail Learn Repeat". Back then, the use of terms such as "F***-up Nights", "Fail fast" and similar terms was still largely limited to the startup ecosystem and was only slowly finding its way into the rest of the corporate world. However, they were in line with the failure culture that was shaped by Eric Ries' 2011 book The Lean Startup (1) - a work that had an enormous influence on me and many other founders. Even today, six years on, I am a big advocate of the ideas in that book. But at the same time, I have the feeling that some of these originally valuable approaches have become distorted in practice.

I have the impression that formats like the "F***-up Nights" have become more of a show - a platform where failures are almost celebrated without any real progress or deep learning resulting from them. So it's a good time to revisit the message of "Try Fail Learn Repeat" and clarify what I really mean - and more importantly, what I don't mean.

I was also stirred by a very interesting article by Anders Indset in Gründerszene, which I fully agree with: "Don't start a startup, start a company" (2) writes the investor and business philosopher.

What does "Try Fail Learn Repeat" mean to me?

The name "Try Fail Learn Repeat" has a very specific meaning for me, which primarily relates to the first word, "try": The point is to have the courage to do things, to try things out - consciously. "Learn" is the second most important word in the name - of course, you should learn as much as possible from every attempt, both in the case of success and in the event of failure. Then it's important to repeat, to try again - to move on if you failed, or to try to build on if you succeeded.

The mistake, the failure, is really a side effect that may or may not happen. And of course you need a positive failure culture - towards yourself, your friends and your family. And of course you need a good culture of failure within your organization.

What TFLR does not mean

To explain what "Try Fail Learn Repeat" means, it is easier to first clarify what "Try Fail Learn Repeat" does not mean:

- "Try fast and for the sake of trying": It's not about blindly trying things just for the sake of trying. Of course I encourage people to try new things - but always with preparation, a clear strategy, and a goal in mind. The "trying" should have a real purpose.

- "Fail fast, fail proudly and use it for marketing": More and more, I observe how failures are staged for publicity. Sometimes it seems to be more about the attention than the lessons learned from the mistakes. In my opinion, failure should first come with humility and inner reflection - not as a marketing strategy.

- "Learn to evade accountability": Unfortunately, admitting to have learned from a mistake is sometimes used as an excuse to avoid accountability. The opposite should be true: Acknowledging mistakes also means facing up to your responsibilities and, depending on the severity, even consider resigning from your position.

- "Repeat making the same stupid mistakes again": Repeating mistakes is the epitome of stagnation. It's not about making the same mistakes over and over again, but about learning new lessons from every failure and implementing them immediately.

What TFLR really means

My approach to "Try Fail Learn Repeat" is as follows:

- "Try after careful preparation": The attempt should be well thought out and targeted. I advocate a lean approach where resources are targeted and used efficiently. You should work hard to achieve success, but not at any cost.

- "Fail nobly and humbly": Everyone fails at some point. The difference lies in how you deal with failure. Learning humbly from mistakes is far more valuable than bragging about them.

- "Learn thoroughly and implement the learnings": Learning should be intensive and thorough, and the findings must be put into practice as quickly as possible. This is the only way to make real progress.

- "Repeat, but with caution": Repetition is inevitable, but it is crucial not to make the same mistakes. Each new cycle should be based on the lessons learned from the previous one.

A good vs. a bad TFLR cycle

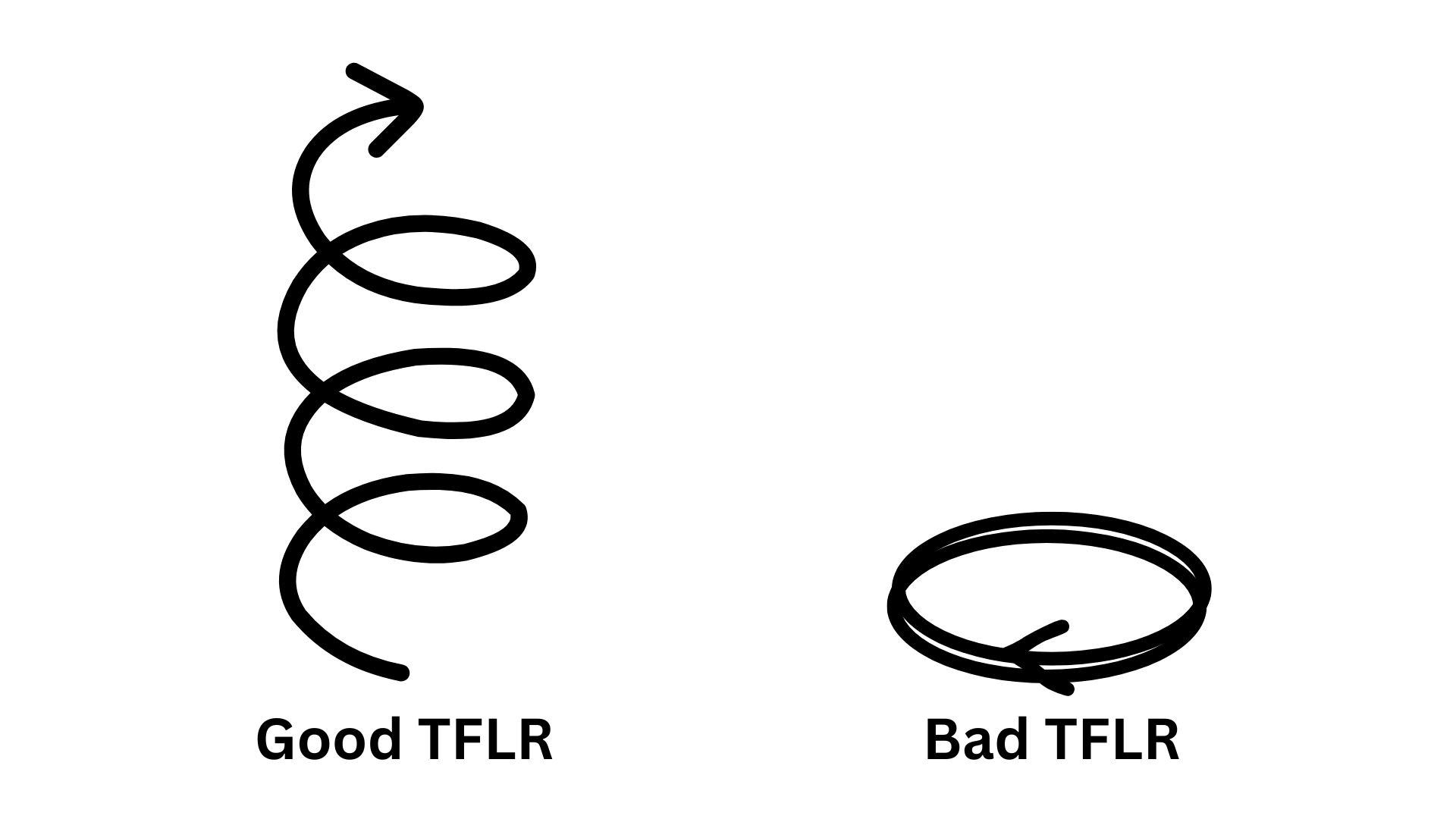

A healthy "Try Fail Learn Repeat" cycle only looks like a cycle when viewed from above - but when you look at the cycle from the side, it's a spiral moving upwards. Each cycle takes a company, a product or yourself to a higher level, with new insights and better understanding.

A bad cycle, on the other hand, also looks like a cycle from above - but in reality you are going round in circles and the company is not moving forward. If mistakes are not honestly analyzed and understood, it leads to a vicious cycle.

How fast should a TFLR cycle be?

The concept of "fail fast" is often misunderstood. It's not about giving up quickly when obstacles arise. Of course, you shouldn't stubbornly try to go through the wall with your head, but I also believe that you shouldn't immediately retreat when difficulties arise.

Instead, I advocate an approach known as "fail cheaply" - in other words, make mistakes without risking high costs. In essence, this means that experiments should focus on small, low-cost steps. Instead of losing yourself in big, expensive failures, you only have the risk of small missteps. The higher the investment, the less willing you are to admit that you have made a mistake. This is often referred to as the "sunk cost fallacy" (3), particularly in the financial sector: The more invested in a project, the harder it is to abandon the investment, even if the project turns out to be a failure.

Large experiments and major "failures" have another disadvantage: they require greater readjustment - what is known as "pivoting" in the start-up world. Although pivoting is seen as a sign of flexibility in the start-up world, it can lead to a lurching course. Projects are simply not thought through deeply enough, in the sense of "If it doesn't work out, we'll just pivot." In addition to the cost and time involved, this creates uncertainty among stakeholders and the team. There is a risk that superficial projects will be lined up one after the other instead of carefully working towards an overarching goal.

Therefore: It's better to go for small experiments and small failures. Basically, the mistakes in a positive failure culture are so small that they would not be worthy of an appearance on a "Fuck-up Night".

Cultural differences in the failure culture

There is no question that the German error culture needs improvement. According to a recent study, 55% of adults under the age of 25 surveyed stated that the culture of error in our society has changed and that mistakes are more socially acceptable. Among the over 55s, the figure is only 34%. Interestingly, the under-25s also find it more difficult to admit mistakes in front of others (52%) - the over-55s find it much easier (31% say they find it difficult to admit mistakes in front of others) (4). In a nutshell: Apparently, young people are perceiving an improved failure culture, but it is difficult to implement.

However, to assume that we only need an error culture like in the USA to solve all our problems is certainly not the last word of truth.

In the US, there is more capital, more " gambling money" available, which makes it easier to quickly make up for even big failures. This availability of capital makes it easier for companies to pursue risky projects and, in case of doubt, to give up quickly and make up for mistakes.

In Germany and Europe, on the other hand, the situation is different. There is less capital available and a single big mistake can not only mean failure, but possibly the end of an idea. This means that mistakes have to be made more carefully. This also has an advantage: if made consciously, this can lead to better planning as well as higher quality and capital efficiency in the long term - an advantage for German and European start-ups that is also recognized by US investors.

Conclusion

For me, "Try Fail Learn Repeat" is not a call to celebrate mistakes. It is about acting consciously and reflectively - not loudly, but quietly and with the objective of truly learning something.

Perseverance and patience are often the keys to success, especially when the goal is quality and long-term sustainability. High investments combined with (too) fast pivots, on the other hand, can also be disconcerting, promote a culture of superficiality and burn capital inefficiently.

Finally, you should always consider the cultural and economic context. With all due respect to the personal and entrepreneurial failure culture: just because mistakes are part and parcel of Silicon Valley doesn't mean that all European founders have to waste their valuable time attending "fuck-up nights". Instead, use this time to learn more deeply!

References

- Ries, E. The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses. (Currency, New York, 2017).

- Indset, A. Warum ihr kein Startup gründen solltet. Business Insider https://www.businessinsider.de/gruenderszene/perspektive/hoert-auf-fehler-abzufeiern-wir-brauchen-wieder-mehr-leistung/ (2024).

- Confirmation bias. Wikipedia (2024).

- Behrens, D. AXA Studie zur Fehlerkultur auf der Arbeit. AXA Deutschland https://www.axa.de/presse/axa-studie-fehlerkultur-im-job (2024).